Gary Becker and perhaps Greg Mankiw, have suggested that because the rise in inequality in the United States results from increases in the return to education, increasing inequality may not be such a bad thing. The argument from the other side has been primarily an effort to point out that the major increases in earnings aren’t going to the roughly 30% of the US workforce that has college degrees but to a select upper

crust.

In either care, however, the increase is not a welcomed signed. Why?

Because, wages don’t come from average product they come from marginal product. That is, we are paid based on how dearly the market wants one more worker just like us. If the gap in wages between college educated and high school educated workers is growing rapidly this is sign that the market is not getting what it wants.

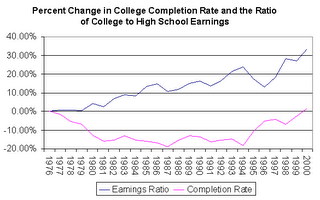

That is the economy would be stronger, growth more robust, technology more advanced, if we had more college educated workers, but we don’t. The market tries to correct this by raising the wage and encouraging more people to finish college, yet until recently more people weren’t finishing college. Now the college completion rate is up but still not by much.

Perhaps more interestingly the gap is seems to be growing because Generation X is starting to reach its high earning years. In the period after the Vietnam War college-going actually declined despite the fact that the returns to college were increasing. Indeed as Card and Lemieux point out, high returns to education seem to result not from strong increases in the demand for skilled workers but in lower supply.

In other words, we are not seeing an increase in the return to education solely or even perhaps even primarily because our advanced economy demands such a highly educated workforce but because our educational system fails to produce a highly educated workforce. It is important to remember that the most vital input to college success, a good K12 education, is not in most cases provided by the market.

Therefore, there is no reason to suspect that we are getting an optimal production of K12 education. Indeed, there are many reasons to suspect that the increasing return to education means that we are producing at a substantially suboptimal level.

This is not a cry for increased funding at the K12 level or drastic measures to curb salary increases among the well educated, but it is a warning about what may be a deep problem in our country.

If the benefits to education are rising but we aren’t getting more educated workers then there must be high marginal costs to education for some of citizens. Understanding the nature of these costs is imperative.

crust.

In either care, however, the increase is not a welcomed signed. Why?

Because, wages don’t come from average product they come from marginal product. That is, we are paid based on how dearly the market wants one more worker just like us. If the gap in wages between college educated and high school educated workers is growing rapidly this is sign that the market is not getting what it wants.

That is the economy would be stronger, growth more robust, technology more advanced, if we had more college educated workers, but we don’t. The market tries to correct this by raising the wage and encouraging more people to finish college, yet until recently more people weren’t finishing college. Now the college completion rate is up but still not by much.

Perhaps more interestingly the gap is seems to be growing because Generation X is starting to reach its high earning years. In the period after the Vietnam War college-going actually declined despite the fact that the returns to college were increasing. Indeed as Card and Lemieux point out, high returns to education seem to result not from strong increases in the demand for skilled workers but in lower supply.

In other words, we are not seeing an increase in the return to education solely or even perhaps even primarily because our advanced economy demands such a highly educated workforce but because our educational system fails to produce a highly educated workforce. It is important to remember that the most vital input to college success, a good K12 education, is not in most cases provided by the market.

Therefore, there is no reason to suspect that we are getting an optimal production of K12 education. Indeed, there are many reasons to suspect that the increasing return to education means that we are producing at a substantially suboptimal level.

This is not a cry for increased funding at the K12 level or drastic measures to curb salary increases among the well educated, but it is a warning about what may be a deep problem in our country.

If the benefits to education are rising but we aren’t getting more educated workers then there must be high marginal costs to education for some of citizens. Understanding the nature of these costs is imperative.

2 comments:

very good post. i came from mankiw's post on the colege premium. your argument certainly casts new light on this phenomenon.

Интересно написано....но многое остается непонятнымb

Post a Comment